The tragedy of the Kent State shootings as seen through an “exiled sculpture” and a military mindset

by Kathryn Monsewicz

“God did tempt Abraham….” reads Genesis 22: 1-18. God ordered Abraham, “Take now thy son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of.”

In the Biblical story, Abraham follows God’s exact orders without question.

Isaac, who carries the wood meant to burn his own body alive, asks his father why they have fire and wood, yet no lamb for the offering. He is unaware of his own demise and Abraham does not reveal his motives.

He builds the alter, binds his son with rope and lays him there. Isaac does not writhe in fear or beg for his life.

And I wonder, in this story, should he have?

Did Isaac, who in this time period would be his father’s successor and follow him as a teacher second only to God, wonder, or fear, for his own life?

In 1970 and today, whose orders have we followed without question — without fear for our own lives, or the lives of others?

_________________________________________

In 1978, a very prominent woman of the art world sat in her Louisiana home, reading about a student protest resulting in hundreds of arrests on the grounds of the May 4 Kent State Shootings. There was a gymnasium to be erected on the site of the tragedy and, as voices called for it to be reconsidered, university officials took to law and order to remove what they saw as an unruly threat. Mildred Andrews was unsettled by the controversy and division that still hung on Kent State’s shoulders. Meanwhile, George Segal, a world-renowned painter and sculptor who taught at Princeton University between 1968-1969, was crafting his usual works of private moments.

He was known for his ability to capture specific human emotion in his sculpture. He would cast plaster molds directly on the bodies of living people, remove it with the same delicacy as a surgeon carving flesh, and piece it back together to recreate the human figure. Rarely did he create work with a political voice or any aura of protest. In 1967, he had created his first protest piece in response to the Vietnam War. Three white bodies laid crumpled on green grass in lifeless peril while a fourth hung from a rope bound at his ankles. There are bullet holes in the wall behind the bodies.

Andrews, a fan of Segal’s work, reached out to the artist and offered to commission him if he would craft a memorial sculpture that she would donate to Kent State University to help heal the wounds that festered there still.

Segal accepted the offer. He traveled to Kent State University to seek out an idea, a sketch in his mind of what the memorial should capture. Looking to compose an appropriate piece that would be accepted by the students and others affected by May 4, he wrote in correspondence to then university president Dr. Brage Golding (1977-1982):

“The theme of “Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac” was provoked by my response to the students and the older people in charge….The fevered encounter between the students and National Guardsmen reminded me strongly of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his only son…because God ordered him to, i.e. he believed in an invisible, difficult abstraction.”

Segal sought a lesson taught throughout history, a lesson engraved in the proverbs of Christian culture, to represent this tragedy of four students killed in the fight for peace in a way that is not a tragedy, but a beautiful work of art.

Segal chose to mold the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac, where God tests Abraham, commanding that he sacrifice his own son, Isaac, to prove his faith in and fear of God. An angel of God would later intervene and halt the execution.

Scripture says, “Abraham stretched forth his hand, and took the knife to slay his son.” But before Abraham can lay sharp edge to soft skin, “the angel of the Lord called unto him out of heaven, and said, Abraham, Lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou anything unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me.”

The angel, a symbol of devotion, peace, and love, intervened at the last moment to prevent blood from being spilled under an order that was not justified by anything other than an abstract idea of fear and of faith.

“The act of the National Guardsmen killing the students was disquieting and horrifying at the moment it occurred,” Segal told the Akron Beacon Journal. “But not too many people remember that Abraham did not have to kill Isaac.”

The National Guardsmen did not have to kill four Kent State students and wound nine others, then, correct?

Most would nod their head, “Yes. This is correct.”

I don’t know.

On one hand, they did not have to kill the students because the intent to harm was not life-threatening. On the other hand, the National Guardsmen were under an oath that if they were ordered to shoot, then that rifle’s trigger was going to be pulled. In a sense, they had to.

But what the tragedy looked like is seen through different lenses. Segal offered his own, based on discussion with witnesses of the tragedy.

“He shows the act of an order being followed versus reluctance. A moral dilemma of obedience and compassion.”

– Kathryn Monsewicz

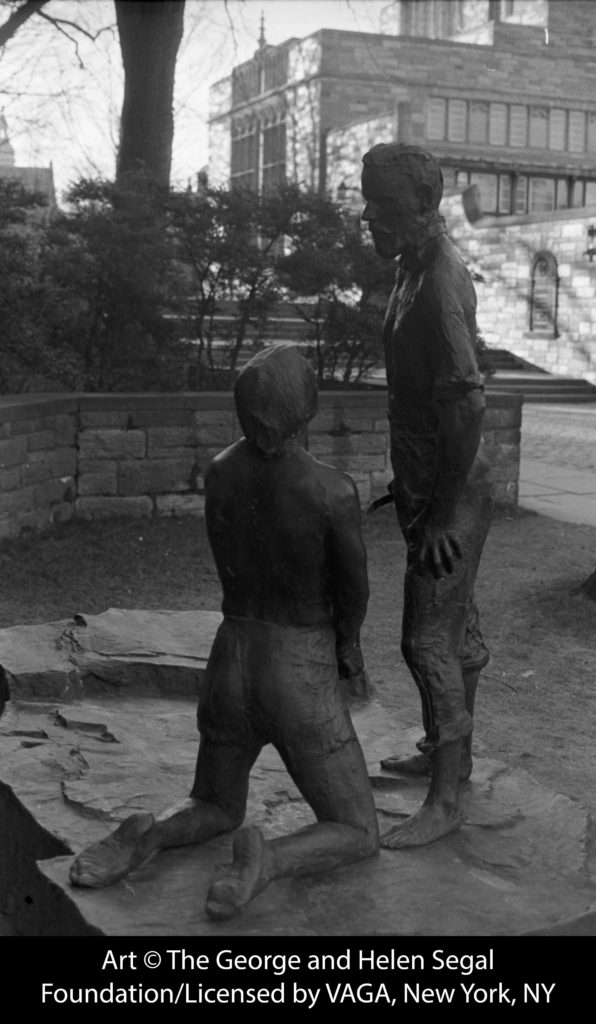

In Segal’s proposed memorial, a tired and worn Isaac, who is bound by rope at his wrists and stripped of his shirt to reveal a bare chest, looks up at his father, Abraham, in a helpless, parted-lip beggary for mercy. Abraham towers above him in an aggressive stance wielding a knife in a closed right fist with his elbow slightly pulled back, yet his left hand shows doubt and skepticism in the orders as it strenuously grips his pant leg. He shows the act of an order being followed versus reluctance. A moral dilemma of obedience and compassion.

Segal’s sculpture was well crafted, and he had a genuinely positive relationship with the May 4 community upon earlier correspondence to decide on his theme. However, campus officials rejected the proposed piece because of issues of accuracy with the metaphor and whether it actually lined up with how they wanted to depict the shootings.

In an article by the New York Times, President Golding’s assistant Dr. Robert McCoy said, “We felt it inappropriate to observe the killing of four students and the wounding of nine others with a sculpture that indicates someone committing violence on someone else. We are afraid that people will see only the violence.”

McCoy, who not only felt the need to lecture Segal on the meaning of the biblical story, made a rather sordid suggestion of the ideal sculpture Segal should craft. He recommended a female coed, nude or semi-nude, “in gentle opposition” as she is threatened by “a vigorous male of 18 or 19 with a powerful bare torso” dressed as a soldier in combat gear. McCoy said both figures would be “performing what they regard as their ‘duty,’ which might serve as a title.”

McCoy’s suggestion was met with abhorrence by not only Segal and Andrews, but also those who were in support of the sculpture and Segal’s artistic independence.

Alan Canfora was one of the leading antiwar demonstrators on campus during the shootings. He was one of the nine wounded, shot through the right wrist, and ever since the tragedy has been very active in the realm of appropriately and adequately commemorating May 4.

“It was a big disappointment,” Canfora said about the rejection of Segal’s sculpture, “another example of KSU insensitivity 1970 through the 1980s.”

Canfora considers the administration of Kent State around the presidencies of Golding and Michael Schwartz (1982-1991) to be insensitive toward shooting victims and their families. Many proposed memorials were either inadequate, inconsiderate, or, sadly, nonexistent. In his 1995 essay, found in the digital commons at La Salle University, he highlights conservative anti-memorial pressures and the administration’s inconsiderate motives on handling the commemoration of the tragedy. Canfora discussed “renowned sculptor” George Segal’s sculpture as well as McCoy’s disrespectful comments and suggestions.

“It was embarrassing for the university, more bad publicity, and I think if you look back on it now, very few people would defend that decision to reject such a beautiful sculpture by the top sculptor of the 1970’s,” Canfora said.

Because Segal was unmoving on changing the theme, the acceptance of the donation at Kent State University was withdrawn.

Segal disagreed with the “too violent” concept of the rejection. He said the work’s theme is “the eternal conflict between adherence to an abstract set of principles versus the love of your own child.”

Abraham looks as if he is going to strike his son in the piece, but Segal noted that, like Genesis 22 in the Bible, Isaac is unharmed. Segal formed this blueprint of the sculpture in his mind out of the motivations of mercy and compassion and, ultimately, peaceful intervention. As God had intervened in the execution of Isaac so should have there been a peaceful intervention with the antiwar demonstrators on campus that day.

Segal had told Canfora that “Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac” was a “healing gesture.”

“It was not meant to be a violent act. It was not depicting an act of violence. It was depicting peaceful intervention to prevent violence.”

– Alan Canfora

“Even though the biblical story talks about the father about to slay his son, at the last moment, God intervened and prevented Abraham from killing Isaac,” Canfora said. “It was not meant to be a violent act. It was not depicting an act of violence. It was depicting peaceful intervention to prevent violence.”

This, Canfora said, is a memorial to what should have happened on May 4, 1970.

“KSU (administration) misinterpreted the sculpture at the time just as an excuse to cover their own mistake and rejection of the beautiful sculpture,” he concluded.

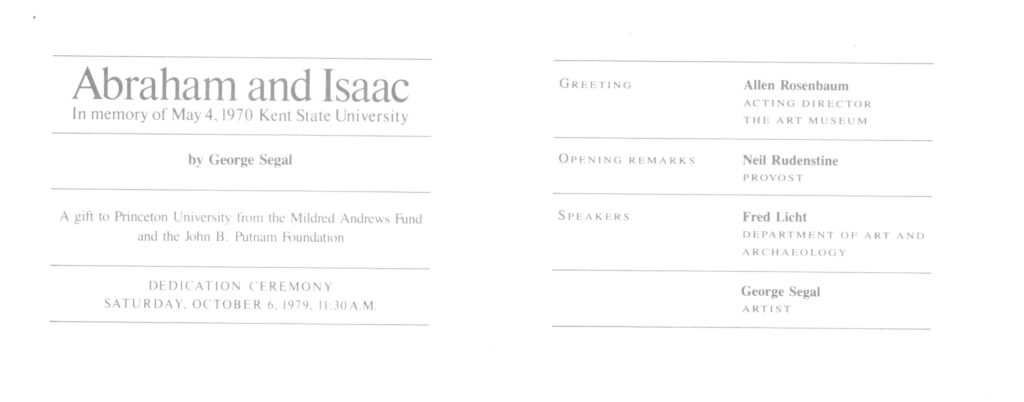

The rejected sculpture was instead taken by Princeton University Art Museum, whose director Fred Licht willingly accepted the work not only for his own admiration of the artist, but because the May 4 sculpture reverberates back to “the monumental origins of sculpture, the possibility it gives us to express our culture and our society.” There, it has been given a permanent home in exile from Kent State University.

Provided by Alan Canfora.

Confusion about May 4 rests in so many young minds, as it did in mine as a freshman who once wrote an article about how sick and tired I was of hearing about May 4. As I hear more people who experienced the tragedy speak out, I have seen where my original thinking lacked sensitivity and understanding. Yet, I have always been left with a clouded question hovering over my head like a rainstorm. If I touched the cloud, I always feared it would erupt in thunder – a controversy that if I shared my opinion coupled with my extreme pride in the United States military, I would instantly be exiled.

I grew up wanting to join the military. I wanted to wear a uniform, carry a rifle, and be a hero. That’s what I knew about my great grandfather, the Marine who had a steel stomach, and my grandfather, the Army sergeant who died in Vietnam in hand-to-hand combat protecting his fellow soldiers, and now my husband, a Marine veteran and my everyday hero. Though I didn’t join, I’ve never lost my faith in America’s fighting force.

Now, I’m a senior in Kent State’s School of Journalism where it is a requirement as a freshman to visit the memorial and study the event. I was an art history major as a freshman and didn’t see the memorial. Now that I have in preparation for the 50th anniversary. I’ve come to understand that people still only see a wolf (National Guardsmen) threatening sheep (the students, victims). They don’t see that this old Biblical saying does not pertain to Kent State. Rather, we have a sheep in wolf’s clothing.

Many still do not understand why National Guardsmen, who were leaving a battle fought on peaceful ground, turned on their heels and pulled the trigger to stain peace with blood.

The Burr, one of Kent’s student media magazines, featured a story in its May 2000 edition that entirely commemorates the shootings. In this edition, Rachel Dissell wrote a piece titled “The Right to Be Afraid” about a former National Guard officer’s perspective of the tragedy. Former Lt. Col. Charles Fassinger, who had been one of the officers ordering a cease fire, spoke on behalf of National Guardsmen who, though they were trained for conflict, could not be trained to ignore the natural instinct of threat to life.

“People question our motives, but the Guard didn’t want to be there either….There weren’t good guys or bad guys – it was just protecting property,” Fassinger told Dissell.

He said you cannot train men to stand in front of a crowd that has become a mob and expect them to handle it without fear or indecision.

Though he understands the feelings of those involved with what happened that day, Fassinger said, “I just hope they can begin to finally understand the Guard and their feelings.”

I believe that the rejection of Segal’s sculpture upon the notion of violent representation goes unguarded against the idea that the Kent State Shootings are often represented and discussed without adequate discourse from the perpetrator of violence.

In a letter to Segal kept by the Kent State May 4th Archives, Rick M. Newton, Assistant Professor of Classical Studies at KSU, writes, “The fundamental issue in the story of Abraham and Isaac, if I was taught correctly in Sunday school, is the testing of a man’s faith in God.” He argues that Segal’s choice of metaphor is not accurate in that the shootings represented man vs. man. Not God. Perhaps, man and state.

“We have in Segal’s sculpture a test of faith. A test of following orders.”

– Kathryn Monsewicz

Many see the Kent State shootings as innocence killed by the system. It is a conflict of man and state. If you narrow into the mind of the National Guardsmen, you’ll see that a National Guardsmen at the time often joined in order to avoid the draft into Vietnam. There were two ways to do so: join, or go to college. Here, we have a battlefield flanked by two sides of the same ideology. In Abraham’s head, there is a test of faith and of fear. In the mind of a soldier who wields a gun is the decision to shoot. It is driven by either his own instinct to pull the trigger or by some other being’s command whom that soldier was taught to follow and to instill faith. Therefore, we have in Segal’s sculpture a test of faith. A test of following orders.

Newton also wrote, “the focus in the Old Testament story is on Abraham and his faith, not on the would-be victim, Isaac.” Isaac was chosen for sacrifice not because of ideas that conflict with Abraham’s or God’s. In fact, the Bible says nothing of Isaac’s ideology. It is purely a test of faith: Does Abraham murder his son and risk the greatest loss of his earthly life to prove his faithfulness to the heavenly Father? The theme, then, would be focusing on the “would-be slayer,” Newton says, and not Isaac, the potential victim – the Kent State student.

In Segal’s sculpture, I see a soldier, not wanting to follow the orders of his higher command to slay the troublemaker who kneels at his feet in pure, voiceless innocence.

To Segal, students of the May 4th tragedy seemed idealistic in their demonstrations against spreading the Vietnam conflict into Cambodia. They disregarded law and democratic processes to fight for radical change. Meanwhile, the generation before had “willingly and altruistically” fought in World War II due to society’s equation of patriotism with obedience.

The parent represented is not Abraham, as one who is only looking at the face of the sculpture might see. The parent that holds the largest representation in this piece is God – the ultimate parent.

Segal’s interpretation as well as my own says that Abraham must decide between following the orders of a higher being that conflict with his own morality and love for a child who is undeserving of harm.

In other words, this is not simply a sculpture commemorating the victims of May 4. Because of my own affiliation with the military, I would enjoy the thought that this is a sculpture for the National Guardsmen.

However, I know this is not the case.

I don’t speak to my husband much about his time in the military, because I know most soldiers have done things they didn’t want to do. Growing up, this was common knowledge for me. My grandfather felt the need to reenlist after the Korean War despite having a wife and children at home. My husband’s grandfather was spat on and had rocks thrown at him upon his own return home from Vietnam, so he doesn’t talk about it at all. The stack of ribbons he hides goes to show exactly what he didn’t want to do.

I listen to my husband when he speaks with his fellow Marines and, sometimes, when he makes a comment that may be unrelated to the situation, but his thoughts are elsewhere.

“You have to follow orders. Even when you don’t want to. Especially when you don’t want to,” he said once, and I heard in his voice something earnest – experiential.

“People are free to offer their own view of the significance and the symbolism of the sculpture,” Canfora said. “But if you go back to what George Segal said himself, I think that should be the definitive commentary of the intent of the sculpture. It was a peaceful statement even though it depicted an act of violence about to occur.”

“Here at Kent State, we have the younger generation also standing up to cry out for peace basically in a situation where the generals and politicians caused the young people to be killed.”

– Alan Canfora

Canfora expanded on Segal’s representation of the Abraham and Isaac generational metaphor:

“It is there to represent the older generation against the younger generation. The father was symbolic of the older generation about the slay the younger generation, which was basically happening in Vietnam. It was the older generals and the politicians sending the young soldiers off to die in war,” Canfora said, “Here at Kent State, we have the younger generation also standing up to cry out for peace basically in a situation where the generals and politicians caused the young people to be killed.”

Segal further explained the generational metaphor.

“In this sculpture, I’ve tried to switch the attention from the youth to the complexities and moral dilemmas of the older man,” Segal wrote in a letter to the university. “If this sculpture can provoke a more thoughtful, introspective attitude on both sides, it will have served some purpose in this larger concern.”

Canfora claims the exact intent of the sculpture was “to express the need for intervention to prevent the older generation from killing the younger generation.” This intervention, of course, like that of God’s hand, needed to be peaceful.

Kent State officials in 1978 did not truly see the depth of Segal’s “Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac.” At first, I thought they were blinded by what the massacre, that was not even a decade before, represented on its face: the unreasoned slaying of an innocent and an unintended result of supposed martyrdom.

Canfora disagrees, noting that the administration was more insensitive to the victims and their families than they were concerned about commemorating the tragedy.

In the summer of 1986, a second donation of an “Abraham and Isaac” sculpture by George Segal was offered to Kent State. Ivan Boesky, a wealthy American stock trader, contacted Canfora as well as Mildred Andrews after falling in love with the original sculpture on Princeton’s campus. He was willing to purchase copies for both Kent State and his own private collection. According to Canfora’s essay, President Schwartz had at first admired the idea, but negotiations had ceased when he “rejected the request of the victim’s families to locate the sculpture near the site of the 1970 killings.” Canfora called it a “petulant decision” to refuse the sculpture a second time. Simultaneously, Boesky was under investigation and later arrested for an insider trading scandal in which he would serve three years jailtime.

Nearly 41 years later, the original sculpture stands on Princeton’s campus labeled by a barely visible and eroding plaque embossed in commemoration to the shootings.

Efforts to return the sculpture to Kent State University’s campus are being made, though they are trivial at best.

Warren Lange, who taught sociology at Kent State from 1975 to 1994, wrote in an essay on Cleveland.com that the sculpture deserves a more rightful placement in situ with the senseless sacrifice of May 4.

Lange wrote, “As we approach the 50th anniversary of this watershed moment in modern U.S. history, it is high time that this thought-provoking work of art be brought home from its foolishly imposed exile.”

Lange had written Canfora an email, requesting his signature on a petition to KSU president Beverley Warren to essentially reverse the rejection and bring the sculpture home.

In the email, Lange wrote, “I was among the KSU faculty members who protested the rejection of the Segal sculpture in 1978, and continue to stand in solidarity with many others in firm opposition to all attempts to deny, distort and/or dilute the colossal and awful meaning of what happened at KSU on May 4.”

He regarded the return of the “exiled sculpture” as making “an important step toward overcoming denial, enhancing enlightenment, and promoting peace.”

Canfora’s response is as follows:

Hello Werner,

Princeton would never surrender such fine art nor should KSU so awkwardly request such a transfer at this late date. All our families of the Kent 1970 casualties attended the meaningful 1979 memorial dedication at Princeton. George Segal expressed his gratitude to Princeton, and we all agreed.

Please reconsider and remove your petition, sir, which would only be a distraction.

As the significant 50th anniversary of the Kent tragedy approaches in 2020, KSU is already in motion planning a grand commemoration. And new books, films and more are set to launch in 2020 as well.

I hope you can see the larger picture and not attempt to magnify one regrettable event back in the late 1970s.

Please reconsider, Werner.

Best wishes to you,

Alan

Lange responded, thanking Canfora for his “surprising” response as well as “heroic efforts in shedding light on the truth of May 4.” He believes the presence of the sculpture on Kent’s campus would make that light shine much brighter than it does in exile at Princeton. He revised the petition, still calling for its return, and was pleased to hear of current KSU efforts in commemorating the tragedy for its 50th anniversary.

If the sculpture could be returned to Kent State, as inconceivable as that might be, it could help peel away the veil of ignorance that National Guardsmen were simply acting in political and generational barbarism and not following orders that the soldiers did not want to follow. It could stir necessary discourse about moral dilemma as well as the necessity for peaceful intervention to prevent violence.

And yet, at the end of Genesis 22, in the eighteenth line, the angel says in God’s name, “And in thy seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed; because thou hast obeyed my voice.”

Perhaps the reward for obedience in the past has finally been met with the need for reason and the question, “Why?”