Hearts that strive for change connect over the the boundary of time.

By Taylor Patterson

By Anu Sharma

I dig my sneakers deeper into the soft slope of the earth, the victory bell visible between my dirt-stained knees. This is where student protestors stood on May 4th, 1970, before they knew of the tear gas, bloodied bullets, the sound of death. I look out over the field, a group of men play lacrosse in blue penny jerseys, a woman tying a hammock between two oak trees.

I think of Allison Krause, her dark and waved hair frizzed from springtime humidity—mine does the same now, sitting on this hill nearly 50 years later. The yellow daffodils are shyly budding; they were planted in 1990, a tribute to the fallen Vietnam soldiers. Grounds keepers return each year to replant them, even though they are perennials, because they want to ensure that the hillside is sprinkled with yellow eulogies. Anytime you search Allison’s name you’ll find her quote beside it, “Flowers are better than bullets.” More than 60 bullet shells would’ve landed alongside Taylor Hall where the dirt separates and springtime grass sprouts. I wonder who searched the field and collected them when campus grew desolate in the following days. Did some of those shells get lost, buried beneath what are now late April buds?

Sometimes dissent is the most powerful way to say that we care about our country and its future.

I have been a student activist and organizer, a link that chains me to the shooting. I probably would’ve curled my knuckles into a fist and stood alongside those students. When I came to Kent State in 2016, I had recently entered the world of activism. I remember my stomach burning the ominous November morning Trump was elected. The air held its breath. That night, students held gloved hands and shouted their fears into the nipping cold through a cheap megaphone. When I first visited the May 4th museum I thought of the strength we shared that November night. The same burning in my stomach returned when I found a clean bullet hole through the metal Drumm sculpture.

Who would I have chanted with on that hillside? I search the internet and Kent’s archives for a connection to the women of that time and their political dissent. I hope that digging through meticulously labeled cardboard boxes will allow me to feel closer to the names and faces of those controversial times, to tether me to their stories through the decades that separate us.

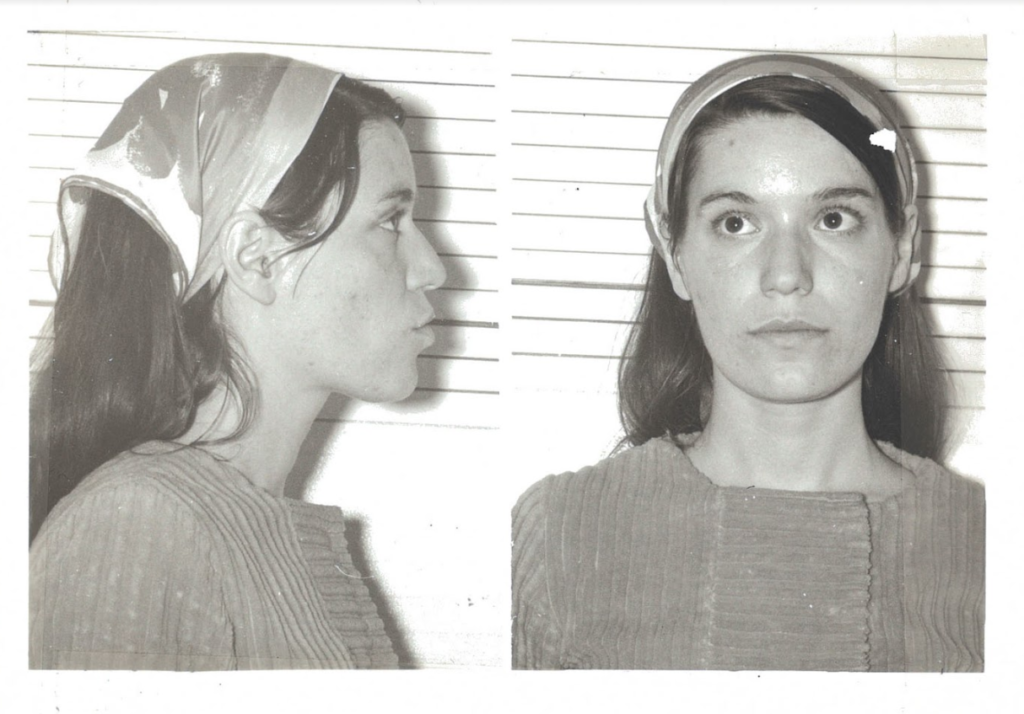

I stare at the black and white photo. A young woman’s brown eyes are focused just right of the camera, hair pulled out of her face with a small scarf. “Charged with Participating in a Riot. Bond set at $200,” is pressed from a typewriter just above Carolyn Erickson’s mugshot. She was arrested April 16, 1969, nearly a year before the shootings. Students for a Democratic Society held an occupation at the Music and Speech Building, hoping the university would meet their demands. SDS first and foremost wanted the university to abolish the ROTC because of its link to militarization and the Vietnam War. Five students were arrested, seven suspended and SDS was revoked of their charter. SDS released a flyer with their demands post-occupation, encouraging students to attend an upcoming rally:

Kent State University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives

“They’re worried. They know people can dig what it is when they get themselves together. We are not worried. We can struggle the whole lot—together…So we got to keep struggling against racism and imperialism wherever we find it. Even in the face of the pig repression they bring down on us. We won and we will again because we dare to struggle.”

Carolyn was willing to get arrested for these demands but was lucky enough that her husband paid her bail. Her record reminded me of an activism training I attended while organizing with Ohio Student Association in 2016, my freshman year. The facilitators drew an imaginary line on the floor and asked those of us who were willing to be arrested during protest to step over it. My young, wobbly legs walked across the line, sweat gathered at the back of my neck—I wasn’t sure if it was the August heat or the thought of handcuffs clicking behind my back. But I did feel a revolution growing inside of me then, and it came rushing back when I found Carolyn’s police report in quiet confines of the 12th floor archives.

Dianne Gallagher was another Kent student who became involved in anti-war activism in 1969. That October she marched in DC with 250,000 others at the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, which led to her standing on Kent Campus after Nixon invaded Cambodia. In a 2010 interview, she revists her past in activism. She recalls her boyfriend’s room being raided after the shootings. “I think it was part of the government’s paranoia at that time,” she said. Whoever raided the apartment thought it was a political organization headquarters.

“There was nothing there except three people, with I’m sure political leaflets and everything, but there was no telephone system, there was no anything to create the kind of fear that was in this country with what they termed the silent majority. They weren’t very silent. So they gave us much more credit. So we became part of that, I became part of that.”

My instinct is to gather the community, to scribble the truth on large sheets of poster paper, to create a plan of action while sitting cross legged on a worn-out rug and munch on delivery pizza.

It was Nixon that coined his followers as the silent majority. This is the same rhetoric Donald Trump used on his campaign trail. In 2015 in Greenville, South Carolina, he said, “Everytime I speak, I have sold-out crowds. Everytime I speak, I have standing ovations—every single time. It’s the silent majority. They want to see wins. They want to see us have victory.”

Dianne is right, they weren’t very silent—they aren’t very silent. In 2017 they raised flaming tiki torches against a muggy August night in Charlottesville, chanting, “You will not replace us.” We are living in a time of political polarization, much like ‘60s. It’s not that this country has forgotten the past, but it’s all too nostalgic for it. Donald Trump advanced off baby boomers longing for the past with “Make America Great Again.” He dug up Nixon’s Law and Order term, which he used to describe protestors in a June 2018 tweet:

“These radical protestors want ANARCHY—but the only response they will find from our government is LAW AND ORDER!”

These aren’t the only tips and tricks he picked up from Nixon’s rhetoric. He also calls protestors at an April 2016 California campaign rally “thugs and criminals.” Sound familiar? Nixon referred to Cambodia invasion protestors as “bums blowing up campuses.”

Nixon and Trump attempted to sway public opinion about civil unrest because they know we the people hold power in numbers. The first time I felt this people-power was at a Tamir Rice demonstration in December 2015. I can still hear the snap of an inverted American flag in the winter wind. There is something unshakable about a community coming together to say: we are here and you will listen. Sometimes dissent is the most powerful way to say that we care about our country and its future. Diane knew this. I find her memories of Kent’s activist history in the archives:

“What I realized was that people were coming to Kent from all over to see where the revolution was. Now when people would say that, I’d think, What are you talking about? What revolution? They said, We heard Kent’s the revolution.”

You’d think with our current political landscape that Kent Campus would still carry that same revolutionary sentiment, but it’s not often that demands are shouted down the brick esplanade—in fact, there are hardly demands at all. I’m still trying to draw conclusions as to why it’s dwindled. Though our politics can mirror the ‘70s at times, students today are in a contrasting college environment. The average loan debt of a 2017 college graduate is $28,650. The sometimes unbearable weight of juggling loan debt, multiple jobs and rent costs could be the why we’ve seen the decline of consistent political activism on campus. Maybe it’s the recent change in the way we consume media. It’s been recognized that the 24-hour, fast-paced news cycle and social media could be a source of apathy or compassion fatigue toward today’s issues. There is a piling load of reasons why Kent State students aren’t occupying buildings and marching on front campus like they used to, but I don’t have all the answers to the one question that ignites curiosity and fear inside me.

I strayed from organizing because of the conflict with journalism. But there are still times while reporting that I find injustices. My instinct is to gather the community, to scribble the truth on large sheets of poster paper, to create a plan of action while sitting cross legged on a worn-out rug and munch on delivery pizza.

The current political environment has painted a red target on our backs for, simply, reporting the facts.

I long for those moments, but I know being a journalist in the time of Trump is still an act of protest. Leading up to the Kent State shootings, Governor Rhodes referred to protestors as “the worst type of people that we harbor in America.” Trump’s rhetoric toward the press is comparable to Rhodes. On multiple occasions he has tweeted that journalists are “ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE!” His words are like rocks thrown into a lake, they ripple. In 2016, Walmart was selling shirts on their website reading “Rope. Tree. Journalist. Some assembly required.” The current political environment has painted a red target on our backs for, simply, reporting the facts.

The sun begins to hide behind the oak trees, and I walk away from the flowering daffodils. I am reminded that four students never made their way home, never again watched the victory bell fade out of view. 50 years ago, their permanent place of rest became the asphalt parking lot. And as I say goodbye to the small pebbles stacked on their memorials, I realize, the only tribute I can give to Allison is to keep resisting.